Territorial and Economic Expansion, 1830–1860

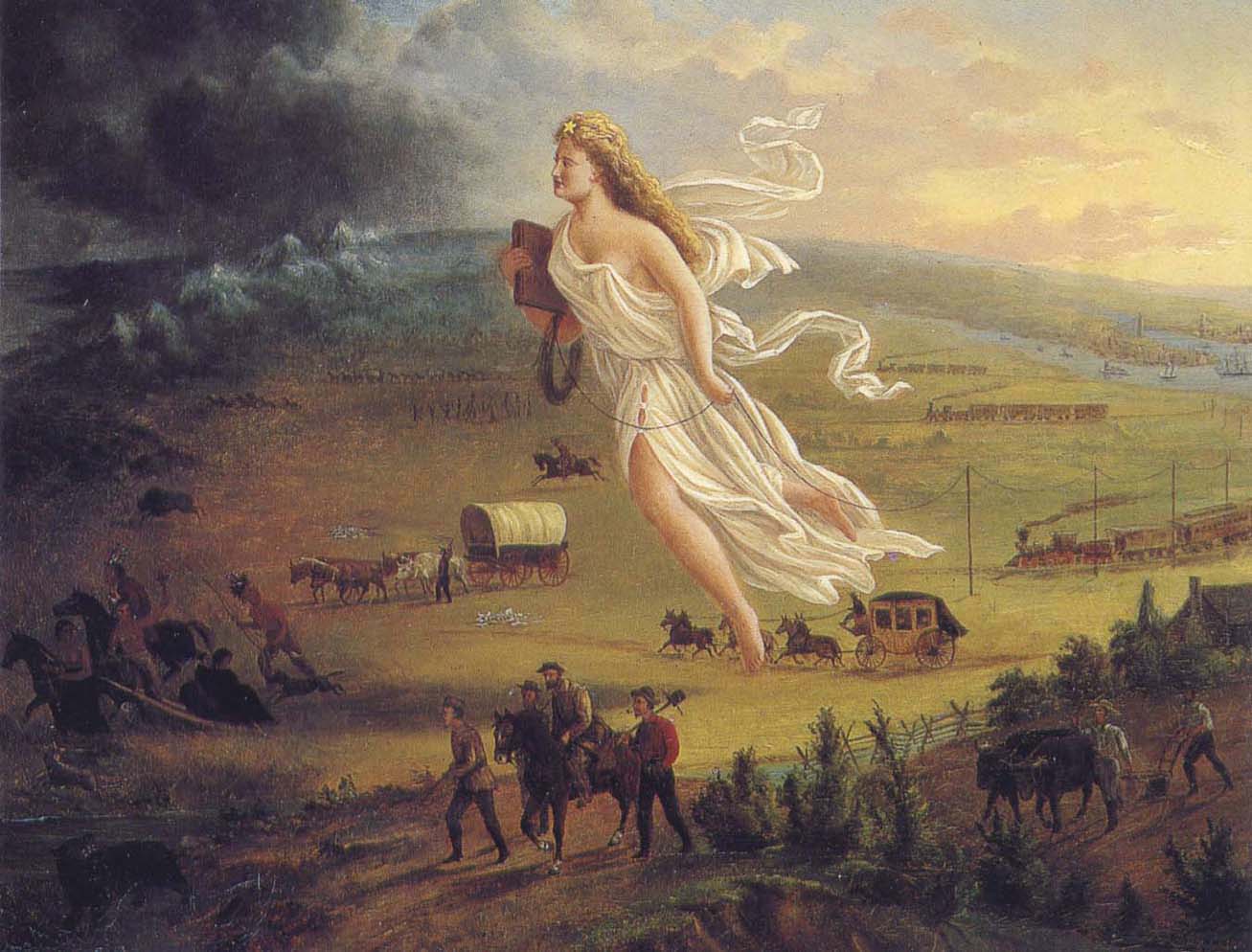

The theme of America’s manifest destiny was used by a host of supporters of territorial expansion after the term was penned by O’Sullivan. It spread across the land as the rallying cry for westward expansion. At first, in the 1840s and 1850s, expansionists wanted to see the United States extend westward all the way to the Pacific and southward into Mexico, Cuba, and even Central America. In a later decade, the 1890s, expansionists fixed their sights on acquiring islands in the Pacific and the Caribbean.

The phrase manifest destiny expressed the popular belief that the United States had a divine mission to extend its power and civilization across the breadth of North America. Enthusiasm for expansion reached a fever pitch in the 1840s. It was driven by a number of forces: nationalism, population increase, rapid economic development, technological advances, and reform ideals. But by no means were all Americans united behind the idea of manifest destiny and expansionism. Northern critics argued vehemently that at the root of the expansionist drive was the southern ambition to spread slavery into western lands.

Conflicts Over Texas, Maine, and Oregon

U.S. interest in pushing its borders southward into Texas (a Mexican province) and westward into the Oregon Territory (claimed by Britain) was largely the result of American pioneers migrating into these lands during the 1820s–1830s.

Texas

In 1823, after having won its national independence from Spain, Mexico hoped to attract settlers—even Anglo settlers—to farm its sparsely populated northern frontier province of Texas. Moses Austin, a Missouri banker, had obtained a large land grant in Texas but died before he could carry out his plan to recruit American settlers for the land. His son, Stephen Austin, succeeded in bringing 300 families into Texas and thereby beginning a steady migration of American settlers into the vast frontier territory. By 1830, Americans (both white farmers and black slaves) outnumbered the Mexicans in Texas by three to one.

Friction developed between the Americans and the Mexicans when, in 1829, Mexico outlawed slavery and required all immigrants to convert to Roman Catholicism. When many settlers refused to obey these laws, Mexico closed Texas to additional American immigrants. Land-hungry Americans from the southern states ignored the Mexican prohibition and streamed into Texas by the thousands.

Revoltandindependence. AchangeinMexico’sgovernmentintensified the conflict. In 1834, General Antonio Lo ́pez de Santa Anna made himself dictator of Mexico and abolished that nation’s federal system of government. When Santa Anna insisted on enforcing Mexico’s laws in Texas, a group of American settlers led by Sam Houston revolted and declared Texas to be an independent republic (March 1836).

A Mexican army led by Santa Anna captured the town of Goliad and attacked the Alamo in San Antonio, killing every one of its American defenders. Shortly afterward, however, at the Battle of the San Jacinto River, an army under Sam Houston caught the Mexicans by surprise and captured their general, Santa Anna. Under the threat of death, the Mexican leader was forced to sign a treaty that recognized Texas’ independence and granted the new republic all territory north of the Rio Grande. When the news of San Jacinto reached Mexico City, however, the Mexican legislature rejected the treaty and insisted that Texas was still part of Mexico.

Annexation denied. As the first president of the Republic of Texas (or Lone Star Republic), Houston applied to the U.S. government for his country to be annexed, or added to, the United States as a new state. Both presidents Jackson and Van Buren, however, put off Texas’ request for annexation primar- ily because of political opposition among northerners to the expansion of slavery and the potential addition of up to five new slave states created out of the Texas territories. The threat of a costly war with Mexico also dampened expan- sionist zeal. The next president, John Tyler (1841–1845), was a southern Whig, who was worried about the growing influence of the British in Texas. He worked to annex Texas, but the U.S. Senate rejected his treaty of annexation in 1844.

Boundary Dispute in Maine

Another diplomatic issue arose in the 1840s over the ill-defined boundary between Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick. At this time, Canada was still under British rule, and many Americans regarded Britain as their country’s worst enemy—an attitude carried over from two previous wars (the Revolution and the War of 1812). A conflict between rival groups of lumbermen on the Maine-Canadian border erupted into open fighting. Known as the Aroostook War, or “battle of the maps,” the conflict was soon resolved in a treaty negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster and the British ambassador, Lord Alexander Ashburton. In the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842, the disputed territory was split between Maine and British Canada. The treaty also settled the boundary of the Minnesota territory, leaving what proved to be the iron-rich Mesabi range on the U.S. side of the border.

Boundary Dispute in Oregon

A far more serious British-American dispute involved Oregon, a vast territory on the Pacific Coast that originally stretched as far north as the Alaskan border. At one time, this territory was claimed by four different nations: Spain, Russia, Great Britain, and the United States. Spain gave up its claim to Oregon in a treaty with the United States (the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819).

Britain based its claim to Oregon on the Hudson Fur Company’s profitable fur trade with the Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. By 1846, how- ever, there were fewer than a thousand Britishers living north of the Colum- bia River.

The United States based its claim on (1) the discovery of the Columbia River by Captain Robert Gray in 1792, (2) the overland expedition to the Pacific Coast by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1805, and (3) the fur trading post and fort in Astoria, Oregon, established by John Jacob Astor in 1811. Protestant missionaries and farmers from the United States settled the Willamette Valley in the 1840s. Their success in farming this fertile valley caused 5,000 Americans to catch “Oregon fever” and travel 2,000 miles over the Oregon Trail to settle in the area south of the Columbia River.

By the time of the election of 1844, many Americans believed it to be their country’s manifest destiny to take undisputed possession of all of Oregon and to annex the Republic of Texas as well. In addition, expansionists hoped to persuade Mexico to give up its province on the West Coast—the huge land of California. By 1845, Mexican California had a small Spanish-Mexican population of some 7,000 along with a much larger number of Native Americans, but American emigrants were arriving in sufficient numbers “to play the Texas game.”

The Election of 1844

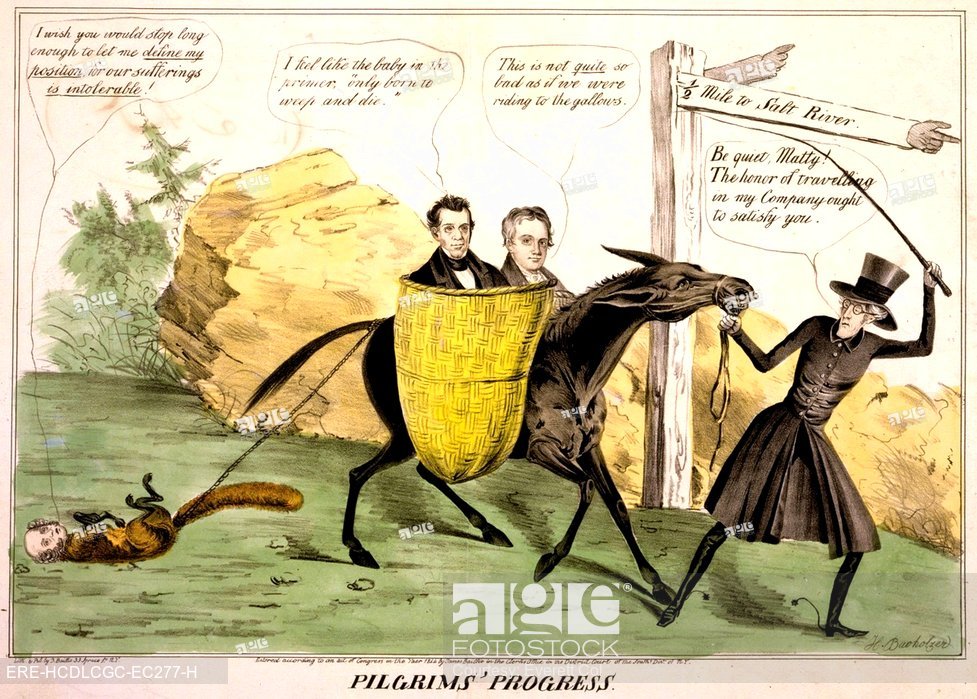

Because slavery was allowed in Texas, many northerners were opposed to its annexation. Leading the northern wing of the Democratic party, former president Martin Van Buren opposed immediate annexation. Challenging him for the Democratic nomination in 1844 was the proslavery, proannexation southerner, John C. Calhoun. The dispute between these candidates caused the Democratic convention to deadlock and, after hours of wrangling, the Democrats finally nominated a dark horse (lesser known candidate). The man they chose, James K. Polk of Tennessee, had been a protege ́ of Andrew Jackson. Firmly committed to expansion and manifest destiny, Polk favored the annexation of Texas, the “reoccupation” of all of Oregon, and the acquisition of California. The Democratic slogan “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” appealed strongly to American westerners and southerners who in 1844 were in an expansionist mood. (“Fifty- four forty” referred to the line of latitude that marked the border between the Oregon Territory and Russian Alaska.)

Henry Clay of Kentucky, the Whig nominee, attempted to straddle the controversial issue of Texas annexation, saying at first that he was against it and later that he was for it. This strategy alienated a group of voters in New York State, who abandoned the Whig party to support the antislavery Liberty party (see Chapter 11). In a close election, the Whigs’ loss of New York’s electoral votes proved decisive, and Polk, the Democratic dark horse, was the victor. The Democrats interpreted the election as a mandate to add Texas to the Union.

Annexing Texas and Dividing Oregon

Outgoing president John Tyler took the election of Polk as a signal to push the annexation of Texas through Congress. Instead of seeking Senate approval of a treaty, Tyler persuaded both houses of Congress to pass a joint resolution for annexation. This procedure had the advantage of requiring only a simple majority of each house. To Polk was left the problem of dealing with Mexico’s reaction to annexation.

On the Oregon question, Polk decided to compromise with Britain and back down from his party’s bellicose campaign slogan, “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” Rather than fighting for all of Oregon, the president was willing to settle for just the southern half of it. British and American negotiators agreed to divide the Oregon territory at the 49th parallel (the parallel that had been established in 1818 for the Louisiana territory). Final settlement of the issue was delayed until the United States agreed to grant Vancouver Island to Britain and guarantee its right to navigate the Columbia River. In June 1846, the treaty was submitted to the Senate for ratification. Some northerners viewed the treaty as a sellout to southern interests because it removed British Columbia as a source of potential free states. Nevertheless, by this time war had broken out between the United States and Mexico. Not wanting to fight both Britain and Mexico, Senate opponents of the treaty reluctantly voted for the compromise settlement.

War With Mexico

The U.S. annexation of Texas led quickly to diplomatic trouble with Mexico. Shortly after taking office in 1845, President Polk dispatched John Slidell as his special envoy to the government in Mexico City. Polk wanted Slidell to (1) persuade Mexico to sell the California and New Mexico territories to the United States and (2) settle a dispute concerning the Mexico-Texas border. Slidell’s mission failed on both counts. The Mexican government refused to sell California and insisted that Texas’ southern border was on the Nueces River. Polk and Slidell asserted that the border lay farther to the south, along the Rio Grande.

Immediate Causes of the War

While Slidell waited for Mexico City’s response to the U.S. offer, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to move his army toward the Rio Grande across territory claimed by Mexico. On April 24, 1846, a Mexican army crossed the Rio Grande and captured an American army patrol, killing 11. Polk used the incident to send his already prepared war message to Congress. Northern Whigs (among them, a freshman Illinois Congressman named Abraham Lin- coln) opposed going to war over the incident and doubted that American blood had been shed on American soil, as the president claimed. Nevertheless, Whig protests were in vain; a large majority in both houses approved the war resolution.

Military Campaigns

Most of the war was fought in Mexican territory by relatively small armies of Americans. Leading a force that never exceeded 1,500, General Stephen Kearney succeeded in taking Santa Fe, the New Mexico territory, and southern California. Backed by only several dozen soldiers, a few navy officers, and American civilians who had recently settled in California, John C. Fre ́mont quickly overthrew Mexican rule in northern California (June 1846) and pro- claimed California to be an independent republic with a bear on its flag—the so-called Bear Flag Republic.

Meanwhile, Zachary Taylor’s force of 6,000 men drove the Mexican army from Texas, crossed the Rio Grande into northern Mexico, and won a major victory at Buena Vista (February 1847). President Polk then selected General Winfield Scott to invade central Mexico. The army of 14,000 under Scott’s command succeeded in taking the coastal city of Vera Cruz and then captured Mexico City in September 1847.

Consequences of the War

For Mexico, the war was a military disaster from the start, but the Mexican government was unwilling to sue for peace and concede the loss of its northern lands. Finally, after the fall of Mexico City, the government had little choice but to agree to U.S. terms.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—Mexican Cession (1848). The treaty negotiated in Mexico by American diplomat Nicholas Trist provided for the following:

1. Mexico would recognize the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas.

2. The United States would take possession of the former Mexican prov- inces of California and New Mexico—the Mexican Cession. For these territo- ries, the United States would pay $15 million and assume the claims of American citizens against Mexico.

In the Senate, some Whigs opposed the treaty because they saw the war as an immoral effort to expand slavery. A few southern Democrats disliked the treaty for opposite reasons; as expansionists, they wanted the United States to take all of Mexico. Nevertheless, the treaty was finally ratified in the Senate by the required two-thirds vote.

WilmotProviso. U.S.entryintoawarwithMexicoprovokedcontroversy from start to finish. In 1846, the first year of war, Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot proposed that an appropriations bill be amended to forbid slavery in any of the new territories acquired from Mexico. The Wilmot Proviso, as it was called, passed the House twice but was defeated in the Senate.

Prelude to civil war? By increasing tensions between the North and the South, did the war to acquire territories from Mexico lead inevitably to the American Civil War? Without question, the acquisition of vast western lands did renew the sectional debate over the extension of slavery. Many northerners viewed the war with Mexico as part of a southern plot to extend the “slave power.” Some historians see the Wilmot Proviso as the first round in an escalating political conflict that led ultimately to civil war.

Manifest Destiny to the South

Many southerners were dissatisfied with the territorial gains from the Mexican War. In the early 1850s, they hoped to acquire new territories, espe- cially in areas of Latin America where plantations worked by slaves were thought to be economically feasible. The most tempting, eagerly sought possibil- ity in the eyes of southern expansionists was the acquisition of Cuba.

Ostend Manifesto. President Polk offered to purchase Cuba from Spain for $100 million, but Spain refused to sell the last major remnant of its once glorious empire. Several southern adventurers led small expeditions to Cuba in an effort to take the island by force of arms. These forays, however, were easily defeated, and those who participated were executed by Spanish firing squads.

Elected to the presidency in 1852, Franklin Pierce adopted prosouthern policies and dispatched three American diplomats to Ostend, Belgium, where they secretly negotiated to buy Cuba from Spain. The Ostend Manifesto that the diplomats drew up was leaked to the press in the United States and provoked an angry reaction from antislavery members of Congress. President Pierce was forced to drop the scheme.

Walker Expedition. Expansionists continued to seek new empires with or without the federal government’s support. Southern adventurer William Walker had tried unsuccessfully to take Baja California from Mexico in 1853. Finally, leading a force mostly of southerners, he took over Nicaragua in 1855. Walker’s regime even gained temporary recognition from the United States in 1856. His grandiose scheme to develop a proslavery Central American empire collapsed, however, when a coalition of Central American countries invaded and defeated him. Walker was executed by Honduran authorities in 1860.

Clayton-Bulwer Treaty (1850). Another American ambition concerned the building of a canal through Central America. Wanting to check each other from seizing this opportunity, Great Britain and the United States agreed to a treaty in 1850 (the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty). It provided that neither nation would attempt to take exclusive control of any future canal route in Central America. This treaty continued in force until the end of the century. A new treaty signed in 1901 (the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty) gave the United States a free hand to build a canal without British participation.

GadsdenPurchase. AlthoughhefailedtoacquireCuba,PresidentPierce succeeded in adding a strip of land to the American Southwest for a railroad. In 1853, Mexico agreed to sell thousands of acres of semidesert land to the United States for $10 million. Known as the Gadsden Purchase, the land forms the southern sections of present-day New Mexico and Arizona.

Expansion After the Civil War

From 1855 until 1870, the issues of union, slavery, civil war, and postwar reconstruction would overshadow the drive to acquire new territory. Even so, manifest destiny continued to be an important force for shaping U.S. policy. In 1867, for example, Secretary of State William Seward succeeded in purchasing Alaska at a time when the nation was just recovering from the Civil War.

Settlement of the Western Territories

Following the peaceful acquisition of Oregon and the more violent acquisi- tion of California, the migration of Americans into these lands began in earnest. The arid area between the Mississippi Valley and the Pacific Coast was popularly known in the 1850s and 1860s as the Great American Desert. Emigrants passed quickly over this vast, dry region to reach the more inviting lands on the West Coast. Therefore, California and Oregon were settled several decades before people attempted to farm the Great Plains.

Fur Traders’ Frontier

Fur traders known as mountain men were the earliest nonnative group to open the Far West. In the 1820s, they held yearly rendezvous in the Rockies with Native Americans to trade for animal skins. James Beckwourth, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, and Jedediah Smith were among the hardy band of explorers and trappers who provided much of the early information about trails and frontier conditions.

Overland Trails

The next and much larger group of pioneers took the hazardous journey west in hopes of clearing the forests and farming the fertile valleys of California and Oregon. By 1860, hundreds of thousands had reached their westward goal by following the Oregon, California, Santa Fe, and Mormon trails. The long and arduous trek usually began in St. Joseph or Independence, Missouri, or in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and followed the river valleys through the Great Plains. Months later, the wagon trains would finally reach the foothills of the Rockies or face the hardships of the southwestern deserts. The final life-or-death chal- lenge was to get through the mountain passes of the Sierras and Cascades before the first heavy snow. A wagon train inched westward at an average rate of only 15 miles a day. Far more serious than any threat of attack by Indians were the daily experience of disease and depression from harsh conditions on the trail.

Mining Frontier

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 set off the first of many migrations to the mineral-rich mountains of the West. The gold rush to California (1848–1850) was followed by gold or silver rushes in Colorado, Nevada, the Black Hills of the Dakotas, and other western territories. The mining boom brought tens of thousands of men (and afterward women as well) into the western mountains. Mining camps and towns—many of them short-lived— sprang up wherever a strike (discovery) was reported. Largely as a result of the gold rush, California’s population soared from a mere 14,000 in 1848 to 380,000 by 1860.

What is often forgotten is that the discoveries of gold and silver attracted miners from around the world. By the 1860s, almost one-third of the miners in the West were Chinese.

Most pioneer families moved west to start homesteads and begin farming. Congress’ Preemption Acts of the 1830s and 1840s gave squatters the right to settle public lands and purchase them for low prices once the government put them up for sale. In addition, the government made it easier for settlers by offering parcels of land as small as 40 acres for sale.

However, the move to western lands was not for the penniless. A family needed at least $200 to $300 to make the overland trip, which eliminated many of the poor and made the trek to California and Oregon largely a middle- class movement.

The isolation of the frontier made life for pioneers especially difficult during the first years, but rural communities soon developed. The institutions that the people established (schools, churches, clubs, and political parties) were modeled after those that they had known in the East or, for immigrants from abroad, in their native lands.

Urban Frontier

Western cities that arose as a result of railroads (see below), mineral wealth, and farming attracted a number of professionals and businesspersons. San Francisco and Denver are examples of instant cities created by the gold and silver rushes. Salt Lake City grew because it offered fresh supplies to travelers on overland trails for the balance of their westward journey.

The Expanding Economy

The era of territorial expansion coincided with a period of remarkable economic growth from the 1840s to 1857.

Industrial Technology

Before 1840, factory production had mainly been concentrated in the textile mills of New England. After 1840, industrialization spread rapidly to the other states of the Northeast. The new factories produced shoes, sewing machines, ready-to-wear clothing, firearms, precision tools, and iron products for railroads and other new technologies. The invention of the sewing machine by Elias Howe took much of the production of clothing out of the home into the factory. An electric telegraph successfully demonstrated in 1844 by its inventor, Samuel F. B. Morse, went hand in hand with the growth of railroads in enormously speeding up communication and transportation across the country.

Railroads

The canal-building era of the 1820s and 1830s was replaced in the next two decades with the rapid expansion of rail lines, especially across the Northeast and Midwest. The railroads soon emerged as America’s largest industry. As such, they required immense amounts of capital and labor and gave rise to complex business organizations. Local merchants and farmers would often buy stocks in the new railroad companies in order to connect their area to the outside world. Local and state governments also helped the railroads grow by granting special loans and tax breaks. In 1850, the U.S. government granted 2.6 million acres of federal land to build the Illinois Central Railroad from Lake Michigan to the Gulf of Mexico, the first such federal land grant.

Cheap and rapid transportation particularly promoted western agriculture. Farmers in Illinois and Iowa were now more closely linked to the Northeast by rail than by the river routes to the South. The railroads not only united the common commercial interests of the Northeast and Midwest, but would also give the North strategic advantages in the Civil War.

Foreign Commerce

The growth in manufactured goods as well as in agricultural products (both western grains and southern cotton) caused a significant growth of exports and imports. Other factors also played a role in the expansion of U.S. trade in the mid-1800s:

1. ShippingfirmsencouragedtradeandtravelacrosstheAtlanticbyhaving their sailing packets depart on a regular schedule (instead of the unscheduled departures that had been customary in the 18th century).

2. Thedemandforwhaleoiltolightthehomesofmiddle-classAmericans caused a whaling boom between 1830 and 1860, in which New England mer- chants took the lead.

3. Improvements in the design of ships came just in time to speed gold- seekers on their journey to the California gold fields. The development of the American clipper ship cut the five- or six-month trip from New York around the Horn to San Francisco to as little as 89 days.

4. Steamships took the place of clipper ships in the mid-1850s because they had greater storage capacity, could be maintained at lower cost, and could more easily follow a regular schedule.

5. The federal government played a role in expanding U.S. trade by sending Commodore Matthew C. Perry to Japan to persuade that country to open up its ports to trade with Americans. In 1854, Perry convinced Japan’s government to agree to a treaty that opened two Japanese ports to U.S. trad- ing vessels.

Panic of 1857. The midcentury economic boom ended in 1857 with a financial panic. There was a serious drop in prices, especially for midwestern farmers, and increased unemployment in northern cities. The South was less affected, for cotton prices remained high. This fact gave some southerners the idea that their plantation economy was superior and that continued union with the northern economy was not needed.

Historical Perspectives: Manifest Destiny

Traditional historians stressed the accomplishments of west- ward expansion in bringing civilization and democratic institutions to a wilderness area. The heroic efforts of mountain men and pioneering families to overcome a hostile environment have long been celebrated by both historians and the popular media.

In recent years, a number of historians have taken a different and more critical view of manifest destiny and U.S. actions in the war with Mexico. They suggest that there were strong racist motives behind U.S. foreign policy in the 1840s and quote extensively from minority voices of the period who had condemned the Mexican War as a plot to expand slavery. These historians argue that there may have been racist motives even behind the decision to withdraw U.S. troops from Mexico instead of attempting to conquer and occupy that country. They point out that Americans who opposed the idea of keeping Mexico had resorted to racist arguments, asserting that it would be undesirable to incorporate large non-Anglo populations into the republic.

As a result of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, historians today are more sensitive than earlier historians to racist language and beliefs. They see the racial undercurrents in the political speeches of the 1840s that argued for expansion into Native Ameri- can, Mexican, and Central American territories. Rather than concen- trating on the achievements of Anglo pioneers, recent histories of the westward movement tend to focus on the following: (a) the impact on Native Americans, who were dispossessed from their lands, (b) the influence of Mexican culture on U.S. culture, (c) the contributions of African American and Asian American pioneers on the frontier, and (d) the role of women in the development of western family and community life.

In addition, we should consider how Mexican historians view the events of the 1840s. As they point out, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo took half of its territory from Mexico. From the Mexican point of view, the war of 1846 gave rise to a number of long-standing economic and political problems, which have impeded Mexico’s development as a modern nation.

From another perspective, the war with Mexico and especially the taking of California were motivated by imperialism rather than by racism. Historians taking this position argue that the United States was chiefly interested in trade with China and Japan and needed California as a base for U.S. commercial ambitions in the Pacific. U.S. policy makers were afraid that California would fall into the hands of Great Britain or some other European power if the United States did not move in first.